Scottish Devolution 1979: How a Fifer changed the vote 40 years ago

Voters faced a double whammy after the intervention of backbench Labour MP, George Cunningham.

Born in Dunfermnline, Cunningham was educated at Dunfermline High School,

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHis amendment, on Burns Night 1978, was hailed as “the most important back-bench initiative in British politics since the war.”

It added a caveat that the bill had to be approved by 40 per cent of the total electorate as well as a simple majority.

The vote on creating a Scottish Assembly took place on March 1, 1979 after a short campaign – one that was a far cry from the colourful and captivating independence referendum in 2014.

You may also be interested in:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt launched locally just one month earlier, and the campaign saw Labour back a Yes vote.

Harry Gourlay, MP for Kirkcaldy, declared: “This Assembly is the brainchild of Labour.”

They found themselves on the same side as the SNP who ignited their campaign with a visit from Margo McDonald who had recently resigned as acandidate to the Westminster parliament because she believed that Scotland’s future lay in building a strong assembly.

When that finally came to pass in 199 and the Scottish Parliament was created, she became one of its most respected and influential figures.

The 40 per cent rule was a major talking point.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn his re-election as chairman of the Dysart and Gallatown branch of the SNP, W. Gilmour said the Scotland Act “abounds with acts of political vandalism” - with that caveat from Mr Cunningham at the top of his list.

He argued that the electoral roll becomes inaccurate by one per cent every month – people moving away, students perhaps appearing twice as they attend college.

Peter Wright, chairman of the SNP’s Kirkcaldy branch told a public meeting: “Scotland needs every possible Yes vote to overcome the iniquities of the 40 per cent rule - a rule whereby the sick, the too lazy and the apathetic automatically fall into the No camp.”

The party committed to an all-out campaign to generate a Yes vote.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAllan MacLeod, constituency PRO said: “We will be going all out to make sure that the case for Yes is put to very household. We will make everyone aware of the importance of voting Yes and making sure the referendum date does not slip by un-noticed”

This, he argued, was a tactic of the No brigade – ”they want to limit TV coverage and are playing a low -key campaign secure in the knowledge that their 40 per cent fraud has biased the result in their favour.”

A different view emerged as Frank McElhone, Under-Secretary of State for Scotland, addressed a meeting at Templehall Community Centre.

He said the 40 per cent rule should be “a spur for people to vote” and repeated the mantra of the day that “devolution is not about separatism – rather it will do more to bring nationalism down the slippery slope into oblivion.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn its editorial, the Fife Free Press noted the “strange bedfellows” on either side and was left “ wondering at times where the line is between genuine conviction and expedience.”

It also came out in favour of a No vote – “for our part we reject the case for devolution as defined in the present Scotland Act.”

Polling day dawned, and the response was muted.

By lunchtime, less than ten per cent had turned out at Fair Isle, while Pathhead recorded fewer than 100 in those first few hours.

Some even missed out altogether.

Residents in Winnifred Street and Massereene Road found they’d been removed from the electoral roll by canvassers who had gone up the streets, noted the refurbishment work behind doing and, wrongly, assumed from the outward appearance that the houses were empty.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

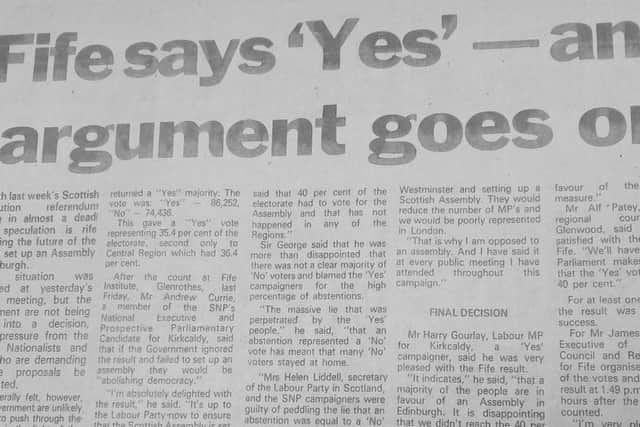

Hide AdBut 65 per cent of Fifers did turn out and vote – and they said Yes.

In fact Fife was the second only to Central in supporting a Scottish Assembly.

It took just five hours to count the votes at Fife Institute in Glenrothes, and any hopes that the majority decision – Scotland wide, 1,230,000 voted Yes and 1.153,000 said No – were quickly snuffed out thanks to the 40 per cent rule.

Sir George Sharp, who went on to lead Glenrothes Development Corporation, was a solid No campaigner, and was in no doubt the result stood.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“You cannot make rules and then allow them to be broken,” he said. “The Bill clearly said 40 per cent of the electorate had to vote for the Assembly and this has not happened in any of the regions.”

At Westminster the minority Labour government decided to abandon devolution, and, in doing so, lost the support of the SNP which helped to prop it up.

The General Election which subsequently followed saw Jim Callaghan defeated, and Margaret Thatcher move into Number 10.

Two decades later, in 1997, Scotland voted once more under a Labour government, and that led to the creation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999.

This time round there was no 40 per cent rule.