The 1974 miners’ strike which led to three-day week and TV stations closing at night

The year was 1974, and the restrictions on use of electricity had a huge impact across the country.

Television stations shut down at 10.30pm, businesses could only operate on specific days and for limited hours, and life was lived by candlelight when the power went out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt was a draconian measure implemented by Prime Minister Ted Heath in a bid to survive a national miners’ strike which ran from January until March.

As a mining town, Kirkcaldy was at the forefront of the dispute.

The dawn of the new year saw ballot papers sent to all miners at Seafield and Frances, but the big concern before anyone downed tools was whether the safety men would also go out.

They were members of NACODS – the National Association of Colliery Overmen, Deputies & Shotfirers – rather than the NUM, and played a crucial role in ensuring the pits were safe.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe very thought of them walking out sparked dire warnings from management.

At a press conference in Edinburgh, James Cowan, Scottish area director of the National Coal Board (NCB) said eight pits were at risk of such action, and Seafield was at the top.

He claimed it could be lost within 10 hours, resulting in a devastating impact on 2000 jobs if the safety men joined the industrial dispute.

It was a stark warning.

“We pump out six million gallons of water a day at Seafield, and the layout of the pit is such that if anything happens to the pit bottom pumping arrangements, and we did not have a safety man we would lose them pit in ten hours”

You may also be interested in:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThere was also strong feeling among miners that if NACODS members were going to benefit from any dispute then they should be part of it.

In the end they agreed not to cross picket lines and lost one month’s wages as a result - and still had their own pay claim to pursue.

With the strike underway, the miners quickly set up soup kitchens to feed those on picket duty.

The dispute had an immediate effect.

Coal supplies dwindled, and local merchants brought in rationing to try to eke out their stocks – they had enough to last a fortnight.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOne bag per customer said John Clark in Bennochy Road, and regulars with an electric fire were told to do without. The Co-op cut supplies too.

Clerical workers at the Frances pit crossed picket lines – only a skeleton staff was supposed to be on duty to ensure hospitals, schools and OAPs get deliveries of coal – while miners were given gifts of wooden logs from merchants to heat their homes.

One month in, and business started to bite back.

The newly formed Kirkcaldy and East Fife Chamber of Commerce sent a telegram to the Prime Minister urging him to reach a settlement.

It said, bluntly, it had no confidence in the way the Government had handled the crisis, and feared the worst for its members and their workforces which numbered some 10,000 people.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey had serious concerns that a two and a half day week - or worse - would cripple industry.

But support among the miners was resolute – some 87 per cent in Scotland voted in favour of action.

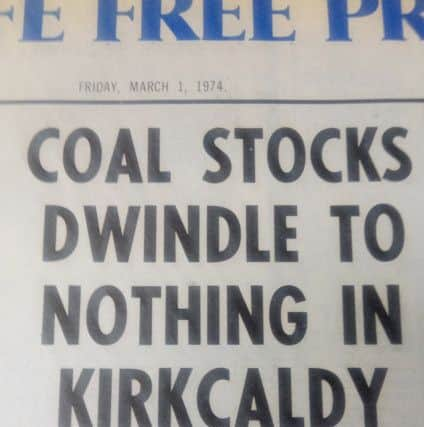

By the end of February, coal supplies in Kirkcaldy had dwindled to almost zero, and hundreds of homes had to do without.

But by March, the strike was over.

The miners’ won and the Heath Government effectively collapsed as the UK went to the polls and delivered a hung parliament.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Prime Minister couldn’t reach agreement with the Liberals to stay in power, and so he was swept out of 10 Downing Street and replaced by Harold Wilson and a Labour Government.

The miners celebrated what William Barclay - a councillor and worker at Frances - said was “an honourable settlement.”

“It doesn’t meet our full claim but I do not anticipate any opposition, “ he said.

A 13-week overtime ban was also lifted as miners backed a new deal which saw face workers get £45 a week basic wage, other underground workers £36, and surface employees £32.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdClerical staff also returned to Frances for some difficult talks. Cllr Barclay said: “I think there could be some recriminations by the men at Frances because the clerks did not join us in our struggle.

“However it is really a problems for the clerks’ own trade union.”

The deal was also welcomed by the Chamber of Commerce. Leo Addison, president, said: “I know of firms throughout Scotland which have been forced to close down because of three day working and the lack of materials, and only time will tell what damage has been done.”

The dispute came to an end with a march through town to the skirl of a pipe band.

A longer, much more bitter dispute was a decade down the road…