Bid to restore 16th century Crail doocot gathers pace

Quite unnassuming in its spot just down from Nethergate overlooking the sea, the Priory Doocot is a small portal into the past.

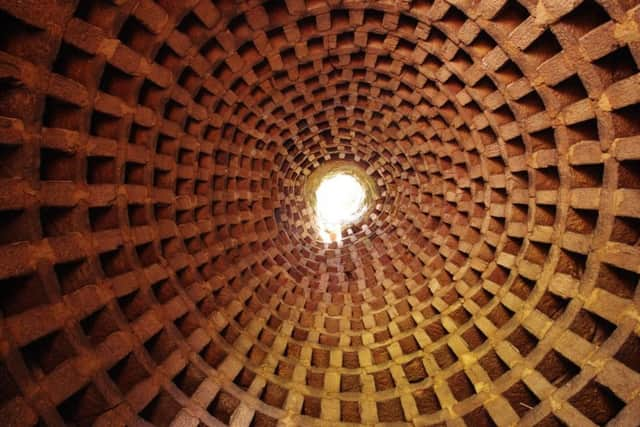

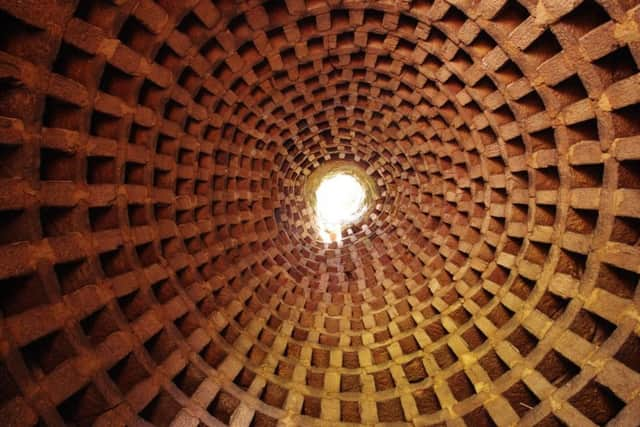

The white beehive-shaped structure – with a tiny door that most folk have to crouch down to enter – is a hugely important piece of history for the town, and one that efforts are being made to retain.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBuilt around the 16th century (although no certain time stamp can be put on it as there are no official materials documenting who actually ordered it to be built), the small doocot has stood the test of time.

Built in stone, it was given a concrete render in the 60s, which although helped to protect the outer structure until today, has played a huge part in the problems now faced by those who want to restore it.

Crail Preservation Society, which acquired the doocot over 50 years ago, is keen to see it open to the public on a daily basis (currently it’s only available during Doors Open Days), with information boards so it can form part of an official Crail heritage Trail, alongside the kirk, town hall and harbour.

But before then, it must be restored, at an estimated cost of £120,000, to ensure it can be enjoyed by generations of locals and tourists.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdSandy Young, of the society, explained: “Building restoration is an exact science that they just didn’t understand in the 60s.

“It was common for concrete render to be used, but it should have been a lime render, which would have allowed moisture to escape.”

For the doocot, damp is the biggest issue.

As well as the concrete render, which means the moisture has nowhere to go, the capstone is missing from the top.

This means rain water is free to enter, plus the gradient of the hill on the north side means one side of the doocot is subject to water from the earth at all times.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut, if successful in its funding application to the Heritage Lottery Fund – Historic Scotland has pledged £38,000 to the project – the Society aims to overcome all of the issues which right now mean an uncertain future for the A-listed structure.

First of all, the concrete render would be removed and a new lime render installed.

Secondly, the entrance to the doocot would be levelled out, coming from the north instead of the south, where it currently is. This would make the path much safer and provide access for those in wheelchairs. Digging out the northside would also eliminate the issue of damp.

Inside the doocot, the missing and broken stones would be repaired, a new floor fitted, upward lighting installed and a new capstone put in place to keep the rain out.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe society would also like to install a potence ladder, which would have been an original feature when it was first constructed.

Five hundred years ago, the doocot provided those who owned it with food throughout the year. Not used for keeping homing pigeons as is often thought, the doocot housed birds which were eaten along with the eggs. It was near impossible to keep and feed cattle throughout the winter, meaning another source of food had to be found, and during the 15th and 16th centuries, the squabs were particular delicacy.

The ladder, which was attached to a pole which went from the ground to the capstone allowed the person responsible for collecting the birds and eggs to climb up inside the doocot, and revolve around the shelves freely.

For Sandy and the other society members, the most important thing is to retain the doocot for years to come, and to allow it to be opened up to the public to enjoy.

“Many people don’t know it’s here and don’t know anything about the history,” said Sandy. “We want to make it something the people of Crail can be proud of.”