This is why high profile music companies are dropping the use of the word 'urban'

This past week, a number of high-profile music companies and brands announced they will be dropping the term ‘urban’ from their products, marketing materials and services.

Milk & Honey – an LA-based music management company whose songwriters have contributed to hits by Dua Lipa and Selena Gomez – announced it would “formally ELIMINATE the term ‘urban’ at our company”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

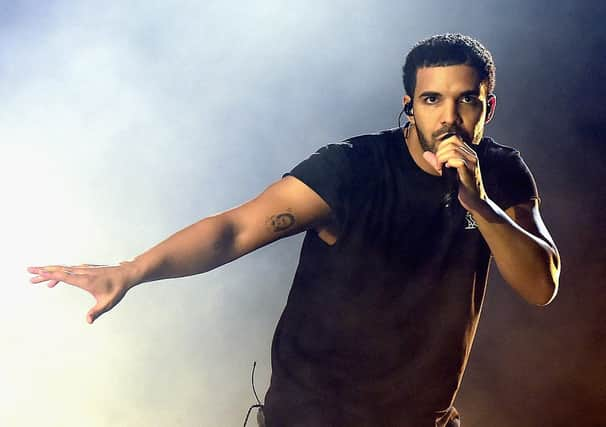

Hide AdRepublic Records – who represent Taylor Swift, Drake and Ariana Grande – also announced it would be dropping the word “urban”.

"While this change will not and does not affect any of our staff structurally, it will remove the use of this antiquated term.”

But why?

What does urban mean?

Googling the definition of ‘urban’ reveals one of two meanings.

The first seems innocuous enough: “in, relating to, or characteristic of a town or city.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBut it’s the second definition given by Google which is causing rather more ire, especially considering recent events.

“Denoting or relating to popular dance music associated with black performers.”

Where does this definition come from?

The more problematic definition of the term actually originated from black New York radio DJ Frankie Crocker.

In the 1970s, he began categorising his eclectic mixes of songs and genres as “urban contemporary”, a term which became shortened to just “urban”.

But in recent years, ‘urban’ has become a lazy byword.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"’Urban' is rooted in the historical evolution of terms that sought to define black music," said Republic Records.

"As with a lot of our history, the original connotation of the term urban was not deemed negative,” said Republic Records.

“However, over time the meaning and connotations of 'urban' have shifted and it developed into a generalisation of black people in many sectors of the music industry, including employees and music by black artists.

Why the change?

On 25 May, George Floyd – an African-American man – was handcuffed and lying face down on a city street as white American Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on the right side of his neck.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe death of George Floyd – and the subsequent protests – has caused uproar throughout the world, drawing attention back to the vast systemic racial injustices within society.

But even before the recent renewed interest in the Black Lives Matter movement, people were campaigning for the change.

In 2018, Sam Taylor – a senior vice president of rights management and publishing company Kobalt Music – told Billboard he “hate[d] the word ‘urban’”, saying, “the word urban to me feels like a project.

“It feels like something that needs to be built. It’s basically like, ‘Oh this urban neighbourhood.’”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It means it’s low-income, not safe, etc. So when you say urban music, to me, it’s letting me know that you think it needs to be rebuilt.

"It's downgrading R&B, soul and hip-hop's incredible impact on music."

In the same year, DJ Semtex – who presented BBC Radio 1Xtra's weekly hip-hop show between 2002 and 2018 – described the word as “a lazy, inaccurate generalisation of several culturally rich art forms.”