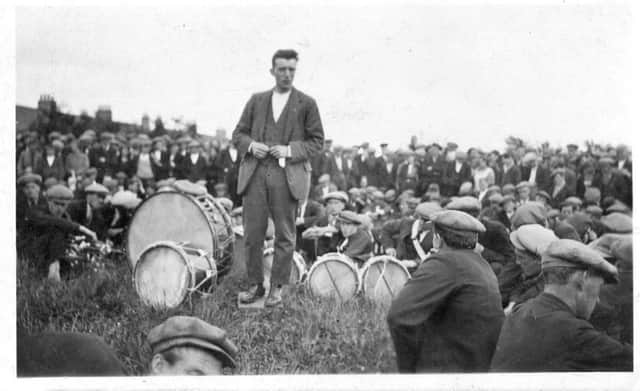

Fife's role in the 1926 General Strike

May 3-12 saw the first and only General Strike in British history.

Called by the Trade Union Congress (TUC) to support the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain (MFGB), close to two million people participated, closing mines, transport services, newspapers, dock yards and power stations. It was a show of defiance like never before.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe industrial action came against a backdrop of tough economic times following the First World War and a growing fear of communism.

The coal industry was suffering immensely. Many of Britain’s richest known seams of coal were used up in the war effort and productivity was down in the mines from its wartime high.

Fife was one of Scotland’s main coal mining areas for hundreds of years, and the industry had a massive impact on people’s working and social lives.

By the start of May, however, thousands of workers had been locked out of their mines.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeetings were held to try and avert the inevitable strike action that was looming. With just two hours to go until midnight on May 3, Labour Party leaders Ramsay MacDonald and Arthur Henderson, met Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, chancellor Winston Churchill and other Tory cabinet members in a last-ditch attempt to stop the strike going ahead.

But all efforts had failed. The miners had had enough. There was never going to be a good time to stand up for their rights – but now was the right time.

Thousands of Fife miners walked out, taking a firm stand against the plans to reduce their meagre wages and worsen their already grim working conditions.

In an act of solidarity, vast numbers from other industries refused to return to work over the next week in a bid to try and force the government to act to prevent the reduction of miners’ wages by 13 per cent and increasing their shifts from seven to eight hours.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn the first full day of action there were estimated to be between 1.5 and 1.75 million people out on strike.

The transport network was crippled without its bus and train drivers, and roads became choked with cars.

The printing presses ground to a halt and food deliveries were held up. The armed forces were quickly moved in to escort and protect food lorries,

Fights broke out between police and workers, mines were stormed and many stood trial on charges of mobbing, rioting and looting. The government reacted aggressively, recruiting thousands of special policemen to deal with the riots by any means necessary.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdStanley Baldwin, appealed to people to trust him in a series of radio broadcasts to the nation.

He said: “I am a man of peace. I am longing, and looking and praying for peace. But I will not surrender the safety and the security of the British constitution. Can you not trust me to ensure a square deal and to ensure even justice between man and man?”

At the same time, the Conservative government was trying to exert greater control over the media to get its message out.

It briefly turned publisher, producing its own newspaper, the British Gazette, edited by Winston Churchill. The Roman Catholic Church also spoke out, declaring the strike “a sin”.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, a growing number of Fifers were becoming volunteers, desperate to get the region back on its feet.

Some helped to get buses back on the roads and trains on the rails, others made sure no one went hungry. It was a touching scene of support for those that fought for their country who were now faced with fighting for their rights.

Nine days after it began, the TUC, which had been holding secret talks with the mine owners, called off the strike without a single concession made to the miners’ case.

The strikers were taken by surprise, but soon drifted back to work. But the resilient miners, deserted by TUC and other supporters struggled on alone for a further seven months.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHowever, by the end of November, most were back down the mines, having to make a choice between striking and starving. Defeated, they returned to work with lower pay and longer hours.

The fight for a better way of life was over.